This is Part 2 of a 2-part blog series. Part 1 covered some history, while this post has three (more) recently published matrices, and the take-home message.

Jumping forward in time, welcome to the 21st century

In Part 1, I showed several networks generated based on some early phylogenetic matrices published in the first volumes of the journal Cladistics. In this post, we will look at the most recent data matrices and trees uploaded to TreeBASE, covering the past seven years.

Nearly a generation later, and facing the "molecular revolution", some researchers (fortunately) still compile morphological matrices. This is an often overlooked but important work: genes and genomes can be sequenced by machines, and the only thing we need to do is to feed these machine-generated data into other powerful machines (and programs) to get a phylogenetic tree, or network. But no software and computer cluster can (so far) study anatomy, and generate a morphological matrix. The latter is paramount when we want to put fossils, usually devoid of DNA, in a (molecular) phylogenetic context. We need to do this when we aim to reconstruct histories in space and time.

Nevertheless, we can't ignore the fact that these important data are (still) far from tree-like. What holds for the matrices of the 80's (see the end of Part 1), still applies now.

So, let's have a look at the three most recent data sets (one morphological, two molecular) published in Cladistics that have their data matrix in TreeBASE.

The morphological dataset

Beutel et al. (2011; submission S11976) provided a "robust phylogeny of ... Holometabola", and note in their abstract: "Our results show little congruence with studies based on rRNA, but confirm most clades retrieved in a recent study based on nuclear genes."

Without having read the study, I can guess which clades (likely used here as a synonym for monophyletic group; but see David's post on Hennig and Cladistics) were confirmed. The data matrix contains: 356 multistate, with up to six states, characters scored and annotated for 34 taxa, including polymorphisms and some gaps ("–") viz missing data ("?"). Just by looking at the Neighbor-net inferred from this matrix. (Standard tree- or network-inference doesn't differ between gaps and missing data, but some people find it important to distinguish between "not applicable" and "not known" in a matrix.)

How did I postulate the monophyla? By deduction: if two or more OTUs are much more similar to each other than to anything else in the matrix, they likely are part of the same evolutionary lineage, ie. have a common origin (= monophyletic in a pre-Hennigian sense). This, when the matrix well covers the group and morphospace, has a good chance to be inclusive (= monophyletic fide Hennig; for the covered OTUs). This is especially so when there is a good deal of homoplasy — the provided tree has a CI of 0.44 and RC of 0.33: convergences should be more randomly distributed than lineage-specific/-conserved traits. The latter don't need to be (or were, at some point in time) synapomorphies, shared derived unique traits, but could be diagnostic suites of characters that evolved in parallel within a lineage and passed on to all (or most) of the descendants.

The first molecular dataset

Let's look at the signal in the two molecular matrices.

In 2016, Gaspar and Almeida (submission S19167) tested generic circumscriptions in a group of ferns by "assembl[ing] the broadest dataset thus far, from three plastid regions (rbcL, rps4-trnS, trnL-trnF) ... includ[ing] 158 taxa and 178 newly generated sequences". They found: "three subfamilies each corresponding to a highly supported clade across all analyses (maximum parsimony, Bayesian inference, and maximum likelihood)."

The total matrix has 3250 characters, of which 1641 are constant and 1189 are parsimony-informative. This is a quite a lot for such a matrix, and, by itself, rules out parsimony for tree-inference. If half of the nucleotide sites are variable, then the rate of character change was high, and parsimony is statistically only robust, when the rate of change was low. High mutation rates or high level of divergence may also pose problems for distance methods and other optimality criteria, all closely related to parsimony.

The file includes three trees, labelled "vero" (which, in Italian, means "true"), "Fig._1" and "MPT". "Vero" and "Fig._1" come with branch lengths; judging from the values (<< 1), they are probabilistic trees (of some sort); the "MPT" is (as usual) provided as a cladogram without branch-lengths. It may be that the authors had to add the parsimony tree just to fulfill editorial policies, while being convinced "vero" is the much better tree. "Vero" is a fully resolved tree (the ML tree?), while "Fig._1" (Bayesian?) and "MPT" include polytomies.

Using PAUP*'s "describe" function, we learn that the "MPT" is 5101 steps long and has a CI of 0.41 and RC of 0.33. Nucleotide sequence data can be notoriously homoplasious, as we repeat the same four states into infinity and have to deal with an unknown but usually significant amount of back mutations. This adds to the other problems for parsimony:

- transitions are more likely to happen than transversions; and

- in coding gene regions, such as the rbcL, some sites (3rd codon positions) mutate much faster than others.

So, the first question is: how different are the three trees provided? Rather than having to show three graphs, we can show the (strict) Consensus network of those trees.

|

| A strict consensus network summarizing the topologies of the three trees provided in the TreeBASE submission of |

The main difference is between "vero" and the other two — "Fig. 1" and the "MPT" are very similar (and both include polytomies). There are three main scenarios for a Consensus network like this with respect to the high portion of variable sites:

- "Fig. 1" is a Jukes-Cantor model-based tree,

- "Fig. 1" is an uncorrected p-distance based tree, or

- most of the variation is between ingroup (the subtree including all Blechnum) and outgroup (the other subtree).

What should ring one's alarm bells are, however, the many grade-like / staircase subtrees, which are unusual for a molecular data set. Staircases imply that each subsequent dichotomous speciation event resulted in a single species and a further diversifying lineage: multiple, consistently occurring budding events.

Let's compare this to the Neighbor-net (usually, I would use model-based distances in such a case, but here we can do with uncorrected p-distances).

The Neighbor-net shows only a limited number of tree-like portions, but does correspond with the main clades above. Only A and B are dissolved, which are the two first diverging clades in the original trees (preceding graph). Some OTUs are placed close to the centre of the graph, or even along a tree-like portion (purple dots), a behaviour known from actual ancestors: some OTUs apparently have sequences that may be literally ancestral to others. This explains the grade structure seen in the original trees. Others (violet dots) create boxes, which may reflect a genuine ambiguous signal, or just be missing data leading to ambiguous pairwise distances. The latter (missing data artefact) is behind the misplacement of the four OTUs (red dots): missing data can inflate pairwise distances severely. And, like parsimony, distance-based methods are more vulnerable to long-branch(edge)-attraction than probabilistic methods.

Model-based distances may help clean up this a bit, but the networks needed for these kind of data are Support consensus networks (see e.g. Schliep et al., MEE, 2017). The split appearance of the Neighbor-net hints at internal signal conflict and, with respect to the high number of variable sites (note the sometimes extremely long terminal edges), saturation issues. Two major questions would be:

- How do the different markers (coding gene vs. inter-genic spacers with different levels of diversity; rps4-trnS is typically more divergent than the trnL-trnF spacer) resolve relationships, which clades / topological alternatives receive unanimous support?

- Does it make a difference to run a fully partitioned (ML) analysis vs. an unpartitioned one vs. one excluding the 3rd codon position in the gene?

The second molecular dataset

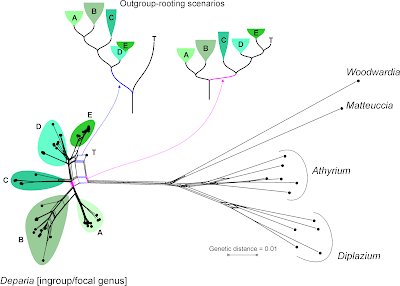

The most recent data are from Kuo et al. (2017; submission S20277), who inferred a "robust ... phylogeny" (see Part 1, Jamieson et al. 1987, and Beutel et al., above) for a group of ferns, focusing on the taxonomy of a single genus, Deparia, that now includes five traditionally recognized genera. In the abstract it says: "... seven major clades were identified, and most of them were characterized by inferring synapomorphies using 14 morphological characters".

The matrix includes the molecular characters used to infer the major clades plus two trees, labelled "bestREP1" and "rep9BEST", both with branch lengths. Branch length values indicate that "bestREP1" could be parsimony-optimized (with averaged or weighted branch lengths), while "rep9BEST" is either a ML or Bayesian tree (technically, it could be a distance-based tree, too, but I don't think such "phenetics" are condoned by Cladistics).

Re-calculated, the first tree ("bestREP1") is shorter (3024 steps) than the one of Gaspar & Almeida, reflecting the much lower number of parsimony-informative sites (979). Many of the sites differ only between the focal genus and the outgroups, which is well visible in the Neighbor-net. [For those of you unfamiliar with Neighbor-nets, a parsimony analysis of these data takes hours, or days depending on the software and computer, while the distance matrix and the resultant Neighbor-net is inferred in a blink.]

Let's remove the distant, long-branching outgroups, which (as we can see in the Neighbor-net) at best provide ambiguous signal for rooting the ingroup — at worst, they trigger ingroup-outgroup branching artefacts. What could a Neighbour-net have contributed regarding taxonomy and the seven major monophyletic intrageneric groups ("clades")? Pretty much everything needed for the paper, I guess (judging from the abstract).

On a side note: by removing the long-branching, distant outgroups, taxon "T" is resolved as a probable member of the putative monophyletic group "5" (= "E" in the full graph with outgroups, and surely a high-supported subtree in any ingroup-only reconstruction, method-independent). Placing the root between "T" and the rest of the genus implies that "5" is a paraphyletic group comprising species that haven't evolved and diversified at all (ie. are genetically primitive), in stark contrast to the other main intra-generic lineages. This is not impossible, but quite unlikely. More likely is the second scenario (primary split between "1"–"3" and "4"–"7"). Having "4" as sister to the rest could be an alternative, too.

This is where Hennig's logic could be of help: find and tabulate putative synapomorphies to argue for a set and root that makes the most sense regarding morphological evolution and molecular differentiation.

The take-home message(s)

We have argued before that it is in the ultimate interest of science and scientists to give access to phylogenetic data. No matter where one stands regarding phylogenetic philosophy, we should publish our data, so that people can do analyses of their own. Discussion should be based on results, not philosophies.

When you deal with morphological data, you should never be content with inferring a single tree (parsimony or other). You have to use networks.

The Neighbor-net was born as late as 2002 (Bryant & Moulton, 2002, in: Guigó R, and Gusfield D, eds, Algorithms in Bioinformatics, Second International Workshop, WABI, p. 375–391; paywalled) and made known to biologists in 2004 (same authors, same title, in Mol. Biol. Evol. 21:255–265), so that authors before this time did not have access to its benefits. Similarly, Consensus networks arrived around about the same time (Holland & Moulton 2003, in: Benson G, and Page R, eds, Algorithms in Bioinformatics: Third International Workshop, WABI, p. 165–176). However, the Genealogical World of Phylogenetic Networks has been here for six years now (first post February 2012). So there is now no excuse for publishing a cladogram without having explored the tree-likeness of your matrix' signal!

Neighbor-nets like the ones I showed in this 2-piece post (or can be found in many of our other posts) are a quick and essential tool to explore the basic signal in your matrix:

- How tree-like is it?

- Where are the potential conflicts, obscurities?

- What are the principal evolutionary alternatives (competing topologies)?

- What is well supported (especially regarding taxonomy and the question of monophyly)?

The second essential tool is the much under-used Support consensus network, not shown in this post but in plenty of our other posts (and many papers I co-authored; for a comprehensive collection of network-related literature see Who's who in phylogenetic networks by Philippe Gambette). Support consensus networks estimate and visualize the robustness of the signal for competing topological (tree) alternatives.

Consensus networks should also be obligatory for those molecular data,where even probabilistic methods fail to find a single fully resolved, highly supported tree.

If the editors of Cladistics are really dedicated to parsimony, they should not still insist only on a parsimony tree (often provided as cladogram), but also parsimony-based networks as well:

- strict Consensus networks to summarize the MPT samples instead of the standard strict Consensus cladograms;

- bootstrap Support consensus networks showing the signal strength and support for alternative trees/competing clades (TNT has many bootstrapping options to play around with); and

- Median networks and such-like for datasets with few mutations, and low levels of expected homoplasy.

This is a problem not limited to Cladistics, but found, to my modest experience in professional science (c. 20 years), in many other journals as well (e.g. Bot. J. Linn. Soc., Taxon, Mol. Phyl. Evol., J. Biogeogr., Syst. Biol., Nature, Science).

Hence, here are my suggestions for future conference buttons, instead of those shown in Part 1.

|

|

|

| No Cladograms! | Use Neighbour-nets! | Support Consensus Networks as obligatory! |

Further reading for those who mistrust trees or become network-curious in general

- In this blog, under the label "EDA" you will find all sorts of data-display / data-explaining networks, biological and non-biological ones; and the labels "neighbor-net" and "consensus networks" will point you to posts using these networks.

- For problem trees – ancestor-descendant relationships, see this recent post and the posts linked there. In this context, don't miss our posts on median networks.

- The label "treelikeness" brings you to posts questioning trees inferred from non-treelike data.

- The labels "cladistics" and "philosophy" include also more conceptual posts in our strife for less tree-thinking and more network-thinking.

- The labels "phylo-networks" and "branch support" collect similar posts on my science-and-other-stuff blog Res.I.P.

No comments:

Post a Comment