This is a joint post by Guido Grimm, Johann-Mattis List, and Cormac Anderson.

This is the second of a pair of posts dealing with the names of domesticated animals. In

the first part, we looked at the peculiar differences in the names we use for cats

and dogs, two of humanity’s most beloved domesticated predators. In this,

the second part (and with some help from Cormac Anderson, a fellow

linguist from the

Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History), we’ll look at two widely cultivated and early-domesticated herbivores: goats and sheep.

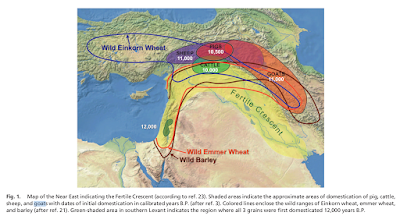

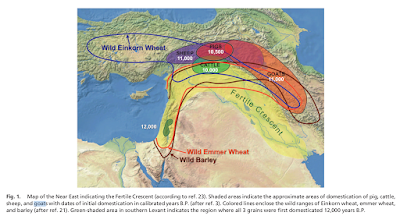

Similar origins, but not the same

Both goats and sheep are domesticated

animals that have an explicitly economic use; and, in both cases, genetic and

archaeological evidence points to the Near East as the place of

domestication (Naderi et al. 2007). The main difference between the

two is the natural distribution of goats (providing nourishment and

leather) and sheep (providing the same plus wool). This distribution is also

reflected in the phonetic (dis)similarities of the terms used in our

sample of languages (Figures 1 and 2).

Capra aegagrus, the

species from which the domestic goat derives, is native to the

Fertile Crescent and Iran. Other species of the genus, similar to the

goat in appearance, are restricted to fairly inaccessible areas of

the mountains of western Eurasia (see Figure 3, taken from Driscoll

et al. 2009). On the other hand,

Ovis aries, the sheep and its non-domesticated

sister species, are found in hilly and mountainous areas throughout

the temperate and boreal zone of the Northern Hemisphere. Whenever

humans migrated into mountainous areas, there was the likelihood of

finding a beast that:

Had wool on his

back and hooves on his feet,

Eating grass on a mountainside so

steep

[Bob Dylan: Man

Gave Names to all those animals].

Goats

Goats were actively propagated by

humans into every corner of the world, because they can thrive even in

quite inhospitable areas. Reflecting this, differences in the terms

for "goat" generally follow the main subgroups of the Indo-European

language family (Figure 1), in contrast to "cat", "dog",

and "sheep". From the language data, it seems that

for the most part each major language expansion, as reflected in the

subgroups of Indo-European languages, brought its own term for

"goat", and that it was rarely modified too much or

borrowed from other speech communities.

There is

one exception to this, however. The terms in the Italic and Celtic

languages look as though they are related, coming from the same

Proto-Indo-European root,

*kapr-, although the initial /g/ in

the Celtic languages is not regular. In Irish and Scottish Gaelic,

the words for "sheep" also come from the same root. In other cases,

roots that are attested in one or other language have more

restricted meanings in some other language; for example, the Indo-Iranic words for goat are

cognate with the English

buck, used to designate a male goat

(or sometimes the male of other hooved animals, such as deer).

The German word

Ziege sticks

out from the Germanic form

gait- (but note the

Austro-Bavarian

Goaß, and the alternative term

Geiß,

particularly in southern German dialects). The origin of the German

term is not (yet) known, but it is clear that it was already present

in the Old High German period (8th century CE), although it was not

until Luther's translation of the Bible, in which he used the word,

that the word became the norm and successively replaced the older

forms in other varieties of Germany (Pfeifer 1993: s. v. "Ziege").

|

| Figure 1: Phonetic comparison of words for "goat" |

Sheep

The terms for sheep, however, are

often phonetically very different even in related languages. The

overall pattern seems to be more similar to that of the words for

dog

– the animal used to herd sheep and protect them from

wolves. An interesting parallel is the phonetic similarity between

the Danish and Swedish forms

får (a word not known in other

Germanic languages) and the Indic languages. This similarity is a

pure coincidence, as the Scandinavian forms go back to a form

fahaz-

(Kroonen 2013: 122), which can be further related to Latin

pecus

"cattle" (ibd.) and is reflected in Italian

[pɛːkora

]

in our sample.

This example clearly shows the limitations of pure

phonetic comparisons when searching for historical signal in

linguistics. Latin

c (pronounced as

[k

])

is usually reflected as an

h in Germanic languages,

reflecting a frequent and regular sound change. The sound

[h

]

itself can be easily lost, and the

[z

]

became a

[r

]

in many Scandinavian words. The fact that both Italian and Danish plus

Swedish have cognate terms for "sheep", however, does not

mean that their common ancestors used the same term. It is much more

likely that speakers in both communities came up with similar ways to

name their most important herded animals. It is possible, for

example, that this term generically meant "livestock", and

that the sheep was the most prototypical representative at a certain

time in both ancestral societies.

Furthermore, we see substantial

phonetic variation in the Romance languages surrounding the

Mediterranean, where both sheep and goats have probably been

cultivated since the dawn of human civilization. Each language uses a

different word for sheep, with only the Western Romance languages

being visibly similar to

ovis, their ancestral word in Latin,

while Italian and French show new terms.

|

| Figure 2: Phonetic comparison of words for "sheep" |

More interesting aspects

The wild sheep, found in hilly and

mountainous areas across western Eurasia, was probably hunted for its

wool long before mouflons (a subspecies of the wild sheep) were domesticated and kept as livestock.

The word for "sheep" in Indo-European, which we can safely

reconstruct, was

h₂ owis,

possibly pronounced as

[xovis

],

and still reflected in Spanish, Portuguese, Romanian, Russian,

Polish. It survives in many more languages as a specific term with a

different meaning, addressing the milk-bearing / birthing female sheep. These include

English

ewe, Faroean

ær (which comes

in more than a

dozen

combinations; Faroes literally means: “sheep islands”),

French

brebis (important

to known when you want sheep-milk based cheese), German

Aue (extremely rare nowadays, having been

replaced by

Mutterschaf "mother-sheep"). In

other languages it has been lost completely.

What is interesting in this context

is that while the phonetic similarity of the terms for "sheep"

resembles the pattern we observe for "dog", the history of

the words is quite different. While the words for "dog"

just continued in different language lineages, and thus developed

independently in different groups without being replaced by other

terms, the words for "sheep" show much more frequent

replacement patterns. This also contrasts with the terms for "goat",

which are all of much more recent origin in the different subgroups

of Indo-European, and have remained rather similar after they

were first introduced.

The reasons for these different patterns of

animal terms are manifold, and a single explanation may never

capture them all. One general clue with some explanatory power,

however, may be how and by whom the animals were used. Humans, in

particular nomadic societies, rely on goats to colonize or survive in

unfortunate environments, even into historic times. For instance,

goats were introduced to South Africa by European settlers to

effectively eat up the thicket growing in the interior of the Eastern

Cape Province. Once the thicket was gone, the fields were then used

for herding cattle and sheep.

|

| Figure 3: Map from Driscoll et al. (2009) |

There are other interesting aspects

of the plot.

For example, as mentioned before, in Chinese the goat refers to the

"mountain sheep/goat" and the "sheep/goat" is the

"soft sheep". While it is straightforward to assume that

yáng, the term for "sheep/goat", originally only

denoted one of the two organisms, either the sheep or the goat, it is difficult

to say which came first. The term

yáng itself is very old,

as can also be seen from the Chinese character used, which serves as one

of the base radicals of the writing system, depicting an animal with

horns:

羊. The

sheep seems to have arrived in China rather early (Dodson et al.

2014), predating the invention of writing, while the arrival of the

goat was also rather ancient (Wei et al. 2014) (and might also have happened more

than once). Whether sheep

arrived before goats in China, or vice versa, could probably be

tested by haplotyping feral and locally bred populations while

recording the local names and establishing the similarity of words

for goat and sheep.

While the similar names for goat and sheep may be

surprising at first sight (given that the animals do not look all that

similar), the similarity is reflected in quite a few of the world's

languages, as can be seen from the

Database

of Cross-Linguistic Colexifications (List et al. 2014)

where both terms form a cluster.

Source Code and Data

We have uploaded source code and data to

Zenodo, where you can download them and carry out the tests yourself (DOI:

10.5281/zenodo.1066534). Great thanks goes to

Gerhard Jäger (Eberhard-Karls University Tübingen), who provided us with the pairwise language distances computed for his 2015 paper on "Support for linguistic macro-families from weighted sequence alignment" (DOI:

10.1073/pnas.1500331112).

Final remark

As in the case

of cats and dogs, we have reported here merely preliminary impressions, through which we hope to

encourage potential readers to delve into the puzzling world of

naming those animals that were instrumental for the development of human

societies. In case you know more about these topics than we have reported

here, please get in touch with us, we will be glad to learn more.

References

- Dodson, J., E. Dodson, R.

Banati, X. Li, P. Atahan, S. Hu, R. Middleton, X. Zhou, and S. Nan

(2014) Oldest directly dated remains of sheep in China.

Sci Rep 4: 7170.

- Driscoll, C., D. Macdonald,

and S. O’Brien (2009) From wild animals to domestic pets,

an evolutionary view of domestication. Proceedings of

the National Academy of Sciences 106 Suppl 1: 9971-9978.

-

Jäger, G. (2015) Support for linguistic macrofamilies from weighted alignment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112.41: 12752–12757.

- Kroonen, G. (2013)

Etymological dictionary of Proto-Germanic. Brill:

Leiden and Boston.

- List, J.-M., T. Mayer, A.

Terhalle, and M. Urban (eds) (2014) CLICS: Database of

Cross-Linguistic Colexifications. Forschungszentrum

Deutscher Sprachatlas: Marburg.

- Naderi, S.,

H. Rezaei, P. Taberlet, S. Zundel, S. Rafat, H. Naghash, et al.

(2007) Large-scale mitochondrial

DNA analysis of the domestic goat reveals six haplogroups with high

diversity. PLoS One 2.10. e1012.

-

Pfeifer, W. (1993)

Etymologisches Wörterbuch des Deutschen.

Akademie: Berlin.

-

Wei, C., J. Lu, L. Xu, G. Liu,

Z. Wang, F. Zhao, L. Zhang, X. Han, L. Du, and C. Liu (2014)

Genetic structure of Chinese indigenous goats and the

special geographical structure in the Southwest China as a

geographic barrier driving the fragmentation of a large population.

PLoS One 9.4: e94435.