Every person who has learned how to read in any language will at some point have to deal with the question of how to pronounce words with unusual spellings. The English writing system offers an abundance of examples; and in my own pronunciation practice of English, I am still frequently corrected by native speakers when mispronouncing words that I know only from books.

For example, what constitutes a big problem for me is the stress on words of Latin origin, which have different stress patterns in German, my native tongue. While we speak of a Theo·rem in German, stressing the final syllable, English pronounces the word as the·orem, stressing the first. But my problems with the English writing system (and probably the problems of many other non-native and native speakers as well) do not usually end with the placement of stress, but may often go much deeper.

Pronunciation

Determining how an unknown word is pronounced in English is very easy nowadays. One can just use one of the numerous online dictionaries, where pronunciations are given in form of sound files. Another, more old-fashioned, alternative is to consult a classical dictionary that illustrate pronunciation with help of the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA 1999). As linguists, we use it on a regular basis in order to compare pronunciations of words across different languages and language families. The original purpose of the IPA, however, was essentially the correct pronunciation for first and second language acquisition; and many teachers were involved in its creation in the late 19th century (compare Kalusky 2017).

Even earlier than the standardization efforts by the International Phonetic Association are ad hoc practices of glossing the pronunciation of difficult words, by comparing them with the pronunciation of more common words in the same language. In order to explain the pronunciation of the English word digest, for example, we could say that word is pronounced as die in dead and as gest in adventure. In the English context, it seems furthermore to be common to make use of some very basic syllables that most people will read and pronounce unambiguously, like ah for the a we find in abacus as opposed the the a we find in and, or toe for the "normal" o-sound we find in no as opposed to the sound of the o in words like to.

That these ad hoc systems, which humans use to gloss pronunciations in writing, are not very reliable can be easily understood when recalling that writing systems have often grown over centuries, reflecting different layers of pronunciation practices applied to words that were imported into the languages at different stages in history. English is, of course, an extremely messy case, but even writing systems like German or Russian, of which speakers would say that the pronunciation is close to the spelling, are far from reaching the explicitness of the International Phonetic Alphabet.

Chinese pronunciation

A particularly interesting case concerns historical glossing practices in the history of Chinese. As I mentioned in an earlier blogpost on networks in Chinese poetry, the Chinese writing system gives only minimal hints regarding the pronunciation of its characters. A character like 手 "hand", which is pronounced as shǒu (or

[ʂɔu²¹⁴] in the IPA), does not tell us anything about its pronunciation;

and even its meaning is difficult to derive from its modern written form.Chinese scholars became aware of the problem rather early, around the 1st century AD when they tried to read the ancient texts produced by their intellectual and poetic masters some 500 years before. In order to make sure that the pronunciation of infrequent characters would not be forgotten over time, they developed different ways to gloss character pronunciations in a more or less systematic manner.

The ancient Chinese scholars didn't have an alphabet to simply transcribe their sounds — intensive contact with Indian phoneticians started much later. So, they started from simple equations, according to which one character was pronounced similarly to another character.

For example, the Shuōwén Jiězì (Explaining Simple and Complex Characters) is an early Chinese character dictionary by the famous scholar Xǔ Shèn (58-148 AD), which was published in 121 AD. In it, the author occasionally uses the formula "read [this character] as X" (in Chinese 读若 dúruò X), in addition to his explanations of the meanings and the structure of the characters. The disadvantage of this duruo method, as linguists often call it (Coblin 1983), is that it only allows glossing of characters for which a simple character with an identical pronunciation exists. It is also not clear whether the formula consistently points to strictly identical pronunciations or whether certain deviations are allowed.

In order to overcome these problems, much more precise ways of glossing character pronunciations were developed from about the 2nd century AD. One of the most interesting glossing systems in this context is the so-called fǎnqiè spellings (Coblin 1983, Branner 2000). This spelling method, which seems to go back to at least the third century, is based on breaking the character pronunciation into two parts, the initial and the final, and selecting one character for glossing each of the two parts — one with an identical initial sound and one with the identical final. If we applied this method to English, we could think of explaining the pronunciation of rice as rye-nice, with rye pointing to the initial sound r and nice pointing to the final of the word.

In the following figure, I have tried to illustrate how both methods (the dúruò and the fǎnqiè method) are applied in concrete examples of text.

Given their straightforwardness and simplicity, fǎnqiè pronunciation glosses became quite popular among Chinese scholars. Even today, people may occasionally use them in order to explain pronunciations without having to rely on foreign writing systems, like the Latin alphabet. As a result, there is an abundance of sources that use this pronunciation device throughout the history of the Chinese language. Although the pronunciation is only given indirectly, with respect to the pronunciation traditions that were active during a given epoch, the fǎnqiè spellings offer great help to explore how the pronunciation of the Chinese language changed over time.

Pronunciation networks

Most of this research on the usage of fǎnqiè spellings has been carried out manually. The first work on fǎnqiè spelling goes back to the early 19th century, when scholars like Chén Lǐ (1818-1882) began to investigate systematically which characters were used to denote certain initial sounds (in Chinese, these are called the upper fǎnqiè characters, fǎnqiè shàngzì 反切上字), and which characters were used to denote the finals (called the lower fǎnqiè characters, fǎnqiè xiàzì 反切下字).

As we might expect, instead of using the same character for the pronunciation of the initial sound all the time, scholars would often alternate the characters, but the alternations were more or less consistent, with some characters being used more frequently and some characters being used less frequently. Scholars like Chén Lǐ figured out that the characters could be classified in a rather rigorous manner which would allow us to reconstruct direct pronunciations of the fǎnqiè spellings.

For example, based on the spellings reported in the Qièyùn, an early rhyme book published in 601 AD, we can say that the characters gōng 公, gǔ 古, gàn 干, etc. were regularly used to indicate initials that would be spelled as

[k] in the International Phonetic Alphabet, while kǒu 口, kě 可, and

kǔ 苦 were used to pronounce [kʰ] (a k with strong aspiration).What I find even more interesting and important than these concrete findings, is that Chinese scholars inherently employed rudimentary network thinking to arrive at their clusters (Gēng 2004). The system of glossed character and glossing character can be easily translated into a system of directed networks, in which we draw a link from the glossing character to the glossed character.

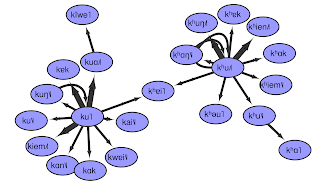

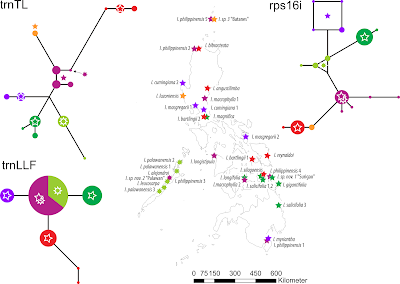

For a talk held earlier during the last year (List 2017), I constructed such a network from the Guǎngyùn (ca. 1000 AD), a later edition of the aforementioned rhymebook Qièyùn, which gives fǎnqiè spellings for more than 20,000 characters. In this network, I concentrated only on the initials, that is, the initial consonants of the language encoded in the source, and constructed a network of all internal relations among the glossing characters. The full network is shown in the following figure.

Eyeballing the network, we can see that the system does look rather systematic. The network is not connected and, apart from a few large connected components, we find a lot of discrete groups that seem to reflect individual initial sounds that were clearly distinguished from other sounds in the fǎnqiè spellings.

The following figure shows a part of the network, namely the second cluster in the big network (above) when going from left to right and staying at the top. In this figure, we can see that the network has two highly connected source characters linking to almost all of the other characters.

I have to admit that I am still having trouble interpreting the network satisfactorily, let alone designing more complex methods to analyse it. Nevertheless, I have the hope that the network analysis of Chinese pronunciation glosses can give us new insights into the phonetic history of Chinese. Importantly, the structures reflected by the network are true pronunciation differences, and that we can indeed find concrete sounds in the indirect fǎnqiè spelling system, becomes specifically clear when comparing the reconstructed pronunciations of the characters in the sample with each other.

For example, when you look at the figure below, you can see that our connected component represents two different clusters of initials, namely a simple k and an aspirated kʰ. The node that links the two groups is given the pronunciation kʰ in our example, but its original reading is ambiguous. The character has two readings and two meanings reflecting both ancient k and ancient kʰ (today pronounced as jiē «Chinese pistachio tree» and kǎi «template», respectively).

Networks of pronunciation glosses in Chinese Traditional Phonology are still under-explored, both with respect to traditional scholarship and with respect to the way they are best handled and analyzed in modern network approaches. If we could develop an approach that would infer the clusters of glosses that point consistently to the same sound, they could give us fascinating insights, not only into the phonological system of Chinese varieties spoken during a given time period, but perhaps also into the dynamics underlying pronunciation changes, when comparing different networks across different times and places.

References

- Branner, D. (2000) The rime-table system of formal Chinese phonology. In: Auroux, S., E. Koerner, H.-J. Niederehe, and K. Versteegh (eds.): History of the language sciences.1.18. de Gruyter: Berlin and New York. 46-55.

- Coblin, W. (1983) A Handbook of Eastern Han Sound Glosses. The Chinese University Press: Chicago.

- Gēng Zhènshēng 耿振生 (2004) 20 shìjì Hànyǔ yǔyīnxué fāngfǎ lùn 20世纪汉语音韵学方法论 [20th century’s methods in traditional Chinese phonology]. Běijīng Dàxué 北京大學: Běijīng 北京.

- International Phonetic Association (1999): IPA Handbook. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

- Kalusky, W. (2017) Die Transkription der Sprachlaute des Internationalen Phonetischen Alphabets: Vorschläge zu einer Revision der systematischen Darstellung der IPA-Tabelle. LINCOM Europa: München.

- List, J.-M. (2017) Network approaches to the reconstruction of Old Chinese phonology. Talk, held at the "Center for Chinese Linguistics" (2017/03/07, Hong Kong, The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology).